Founding India’s first bank for women, by women, she’s turning them into entrepreneurs with small collateral-free loans: Chetna Gala Sinha

Chetna Gala Sinha, a crusader and feminist, believes in the power of micro finance, to turn the fate of a woman and her village around

Chetna Gala Sinha, a crusader and a feminist, believes in the power of microfinance, to turn the fate of a woman and her village around.

Much akin to her idol Jayaprakash Narayan’s brand of dissent, Chetna Gala Sinha’s exponential activism also aimed at ‘total revolution,’ but one that reflects in the quality of life of each of its foot soldiers. Therefore, this khadi-clad crusader with her signature bindis, tailored her Mann Deshi Mahila Sarkari Bank’s schemes to meet the needs of everyone, from the disgruntled woman whose husband broke her piggy bank to that of the vegetable vendor who needed umbrellas to survive the scathing heat.

And her impassioned speeches in her unmistakeably fervent and child-like manner, which are about bringing vocational and economic agency to over 110,000 rural women, are narrated through the stories of a Nandini Lohar, a class-six dropout who now sells framed posters. Or Nakusa, an illiterate abandoned girl who now owns agricultural land. Or even Shamshad Tamboli, once a paltry construction worker in Mumbai, who now runs a sewing school.“I would dream about ‘total revolution’ and how people should seize power when my activism was centred in cities such as Mumbai. But the more time I spent in Mhaswad, the more I realised, that meaningful change came down to rudimentary, individual issues such as not having toilets. What was required were smaller, daily interventions,” says Sinha.

She was raised in Mumbai’s Null Bazar in the upper storey of one of those quintessential neo-gothic structures, which also housed the Kutchi business family’s wholesale kirana shop. Sinha studied commerce at the Lala Lajpat Rai College of Commerce and Economics, and completed her Master’s in Economics from the Mumbai University.

When the Emergency was declared between 1975 and 1977, Sinha was 17. Jayaprakash Narayan, the face of the class struggle in the country, was urging students to shed apathy and march against the powers that be. At Mumbai University, Sinha joined Chhatra Yuva Sangharsh Vahini which was sympathetic to this call, driven by curiosity and a growing desire to be a more consequential citizen.

It wasn’t long before the daily motions of the JP Movement shaped her political person. By the time she was 22, she had traversed through an impressive cross section of the country — as far as the divergent Patna and Gaya in the east, and the powerhouse New Delhi in the north. “My family was proud and scared at the same time. When I was 23, I spent 13 days in the Yerwada jail for campaigning to change the name of ‘Marathwada University’ to ‘Ambedkar University.’ I wrote my father a letter from jail stating why I hadn’t been home in 13 days, and about all the books I was reading. Receiving a document with a Yerwada stamp would have been shocking for him, but he never asked me to pull out. They did worry about my marriage but they never imposed restrictions — more importantly, because they knew that I would never listen. They always thought I was a headstrong feminist,” she says.

The same year, she was summoned to the drought-prone village of Mhaswad in Maharashtra’s Satara district. An encounter with a certain local leader, Vijay Sinha, who was striving to create better opportunities for youngsters who would otherwise migrate, ushered in the next big chapter in her life. “I saw him organising thousands of people for protests, how powerful and passionate he was too, and we fell in love,” she says.

It was 1986-87, and she was teaching intermittently at the SNDT Women’s University while still being a prominent pillar of the JP Movement, when she and Vijay decided to “join forces” and tie the knot. “I had decided to stay in Mumbai, as I wasn’t sure if village life was for me. Luckily, I’m not the kind that overthinks, I jump into things very passionately. We figured we’ll make it work,” she says.

The young couple initially went the distance, but it wasn’t long before the nearly eight-hour-long commute just to see each other got onerous. “When I would sit at the bus stop with no means of communication and the buses would be late by hours, I would get impatient. So, I finally decided to shift base to Mhaswad,” she says.

Vijay’s was a family of farmers, and the young wife arrived prepared for a diametric shift in her way of life and her line of work. The couple borrowed money to grow onions on their five-acre farm, but the vegetable prices plummeted and the two failed to recover even their cost. While she had another vocation to fall back on, Sinha couldn’t help but wonder about the plight of those around her who didn’t, and had everything riding on the earnings from the produce. The next incident came as the final straw.

She had approached several nationalised banks in nearby towns for a loan to procure goats. “I realised how difficult it is to be a farmer. Your liquidity is severely impaired. When you’re from a business family, you’re turning away agents desperate to sell you loans by the dozen, but here, where finances are actually required, genuinely needy applicants are turned away,” she says.

Sinha worked on research projects on rural issues for Australian Aid and the Norwegian Agency for the Development Cooperation, but all along, she felt a constant urge to do something for the villagers, more so the women, who had little financial or social agency. Sinha began organising women for smaller projects such as demanding toilets or power. “My house had become somewhat of a centre where women would come to vent. Yet, not a single person ever asked for money directly — that’s not how they think. They simply want opportunity,” she says.

Inspired by Elaben‘s (Ela Bhatt) SEWA model of self-help groups (SHG), Sinha urged the women of Mhaswad and the neighbouring towns and villages to also organise themselves into a similar format, and started a general credit cooperative society. Women would borrow from the pool to buy goats and buffaloes mainly, and would pay it back through weekly instalments, and unfalteringly so, lest they be ousted from this support system.

In 1995, Bhatt herself, impressed with Sinha’s work in Mhaswad, suggested that she establish a cooperative bank — categorically to meet the special needs of women. “I knew I had to, and I wanted it to be as formalised as possible because it was a financial institution,” she says.

However, the first blow came when the ambitious proposal — made by the members of the 550 SHGs rounded up by Sinha — was turned away right off the bat based on one small technicality. It was rejected because most of the women stakeholders were illiterate. Disheartened but determined not to go down without a fight, Sinha resolved to return with that box checked. In three months, the women came back not only with the skills to read and write, but also make spot-mathematical calculations without a calculator.

In February 1997, with 840 members, all women, contributing a share capital of Rs.600,000 and the necessary paperwork and approvals in place, they procured their licence from the RBI. Today, the Mann Deshi Bank, with nine branches, has a working capital of more than Rs.1.5 billion. “We lend Rs.670 million annually, and will become a Rs.1-billion bank this March,” she informs us.

This success stands in stark contrast to the inaugural day. “Pramila Dandavate (prominent socialist leader) was to come down for the inauguration; this was one of the largest events the village had seen. A huge stage was set — but on the previous night, a local leader, drunk on wine, went around proclaiming, ‘Aata ya baykanchya naavane bombla’ spewing poison like, ‘this girl has come from Mumbai and she will run away with everyone’s money’ and so on. The husbands forbade their wives from attending the event, but we went on our two-wheelers, door-to-door, to convince them. The next day, I was surprised to see that almost 5,000 women attended the launch ‘unescorted’ by the men. They proudly proclaimed that they will hold shares of this bank,” she says.

For the first five years, the women willingly forwent dividends so that the bank has stronger reserves for emergencies. “That’s the reason the organisation has been able to build on its own — its all-women savings, and women-generated capital,” she says, her eyes welling up.

Day zero itself granted her perhaps her most important learning. “When someone is aggressively against a cause you are championing, you gather strength and fight them. But if someone is laughing at you and being patronising, how do you react? At the launch, I saw how to counter it. I learnt that I must use fanfare, flamboyance, it gives the participants pride and dignity about associating with the cause,” she says.

The Mann Deshi, primarily started for savings, constantly adapted to local needs. “We had to provide doorstep banking because women still refused to come to the banks. I ordered 5,000 colourful boxes with Mickey Mouse print, which were to be collected by a field officer from the houses when they fill up. The money would then be transferred to the savings account. In eight days, a woman came with a broken box, asking, ‘Whose stupid idea was this? My husband broke this box and took away the money’. I understood — more than convenience, women needed complete control. They didn’t speak of needing money, they spoke of wealth generation,” she says.

They immediately began working on a microcredit product — that is, a mechanism to provide small loans to poor, unemployed women who do not qualify for traditional credit. “We listened closely to their needs. Street vendors who would sell in the scorching sun every day, and then get sick especially in the summers and lose out on their working days, became our main initial clients and we granted them loans for umbrellas. We would customise the loans for goats, chickens and cows,” she says. To boost efficiency, the bank was computerised at the get-go. “It cost us Rs.200,000, but I wanted the bank to be as modern as any other.” Within three years, the bank recovered its original overheads.

Initially, she wanted to hire staff from larger banks in cities, but no one was willing to move to the village, so, she started looking inward and discovered immense promise. After deploying them to training camps organised by government agencies, she developed a highly competent, completely local staff, which also eliminated the possibility of attrition.

‘Hisaab, hunar aur himmat’ became the war cry, as she registered the Mann Deshi Foundation, for women to advance their societal status through education, governance or business.

Since the 73rd amendment had been implemented, she started training women for the political line of fire. Sinha readied the first woman sarpanch to not only govern effectively, but also stand up to her own husband, who she had anticipated would demand to be seated in her sarpanch chair during proceedings. The Foundation decided to take all its solutions to the doorstep — which inspired the “Business School on Wheels”. The state-of-the-art bus travels with computers and micro ATMs, and has the provision to not only impart direct vocational skills such as screen-printing, chutney-making, and bag-making, but also a ‘Deshi MBA’. “Confidence building, financial literacy, spoken English and basic computer skills are taught, and any woman can join any day,” says Sinha. Half a million women have been trained through this initiative, across Silvassa, Hubballi, Dharwad, Chiplun, Pune, Nashik, Satara, and Kolhapur.

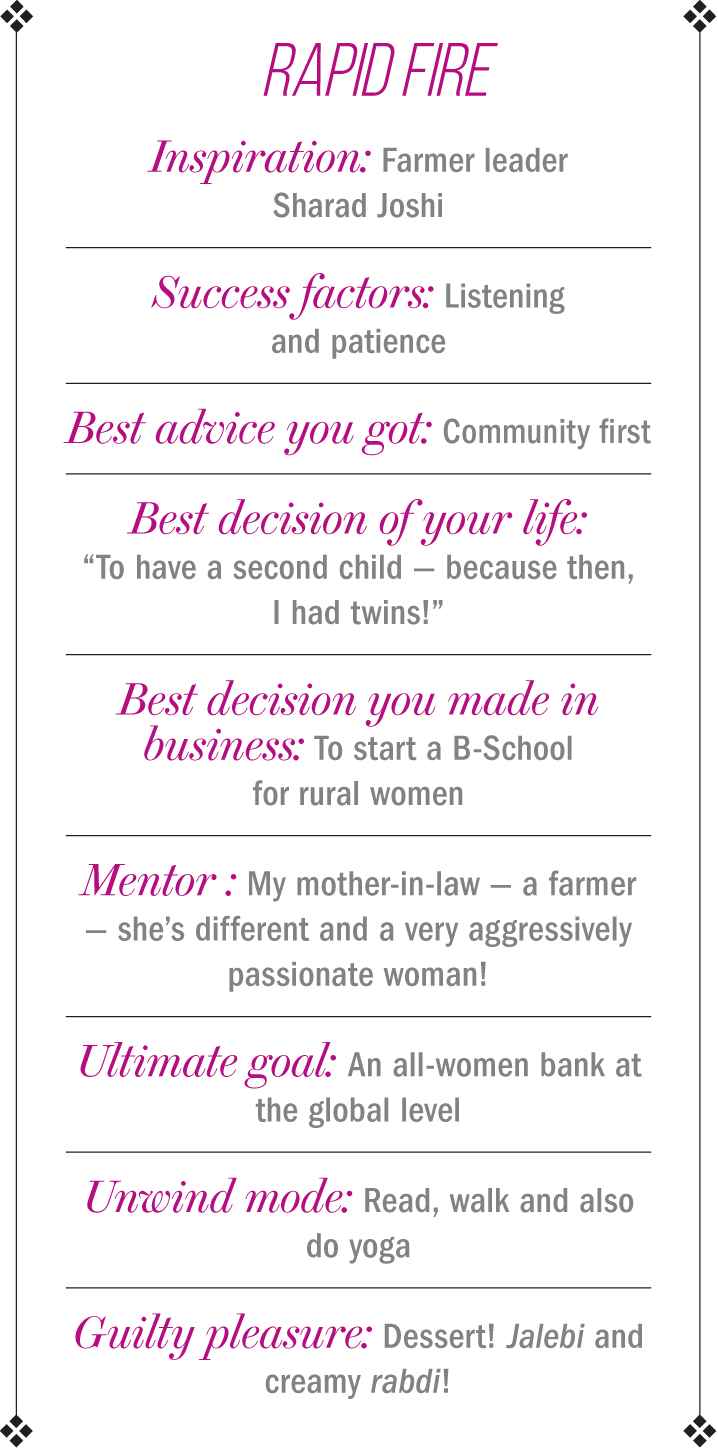

This archetypal Indian ingenuity was recognised alongside Harvard Business School and Fuqua School of Business in a Financial Times’ ranking of the best B-schools in the world. Global plaudits stream in for an unapologetically local solution, bringing Sinha closer to her ultimate goal of building an all-women bank at the global level someday.