Fierce feminist

Monisha Behal’s larger-than-life experiences went hand-in-hand with her impactful social research

At the age of 11, a young Monisha Behal was helping army jawans and victims of the Sino-Indian war of 1962, when the citizens of her hometown Tezpur received an evacuation letter. The Chinese invaders were just 40 miles (about 65 km) away, but Behal and her mother refused to leave. The co-founder of North East Network has lived an adventurous life. When not helping her mother — an active member of the Tezpur Mahila Samiti, a co-operative organisation — she would run off to play with the animals in her neighbourhood. The outdoorsy little girl had ample intellectual stimulation too. Born in 1951, into a family of writers, filmmakers, poets and activists, she had an early exposure to different cultures. “A lot of people visited us, even from rural areas. There were poetry and literary sessions at home,” recalls Behal. Going around with her mother, meeting women from different walks of life was a major influence on Behal.

Even when she was eight, in 1959, Behal was in the thick of political activities such as resettling Tibetan ‘refugees’, a term she says she is not comfortable with, in Missamari. The women from the Samiti, on this side of the border, stitched blankets, gathered food and clothes for them, as a gesture of friendship. Behal too went with them.

Even when she was eight, in 1959, Behal was in the thick of political activities such as resettling Tibetan ‘refugees’, a term she says she is not comfortable with, in Missamari. The women from the Samiti, on this side of the border, stitched blankets, gathered food and clothes for them, as a gesture of friendship. Behal too went with them.

She noticed early on that, although the Northeast seemed a better place for women — with less casteism and gender bias, and strong co-operative networks as compared to other states — reality was different. Women were partially independent through their weaving work in co-operatives, but weren’t allowed to step outside their homes. Many had survived domestic and sexual abuse, and worked for lower wages on farm lands.

Resolving these and working to improve on other areas, such as better sanitation, gender responsive budgeting and equality in governance, would soon become the motto of Behal’s life. Her brand of feminism, she says, is “liberal”. She would rather use her research and numbers to sensitise people, than give in to empty sloganeering and public protests.

Love for research

Influenced by women’s rights movements by Ela Bhatt, founder of Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) and co-operative organiser, and her personal interest in government’s policy making, Behal took up the role of researcher at a young age. In 1974, she did her first major research on the Wancho tribe when she visited Tirap district of erstwhile NEFA (North-East Frontier Agency) now in Arunachal Pradesh with her friend. The study was on the exiled villages, where a few members of the tribe lived after being ostracised. Although Behal had simply accompanied her friend, a researcher, she ended up doing her own study.

She moved to Darjeeling in 1960 to study at Loreto Convent but, every time she visited Tezpur for vacations, she would go to the nearby villages and interview people. She even maintained a diary of frequent shutdowns here, a result of rampant insurgency.

Behal was bitten by the activism bug during her time in Delhi as a student. In the early and mid-70s, as a student, she was influenced greatly by the leftist movement and began reading up on it. She did her BA in Political Science from Indraprastha College for Women followed by an MA and PhD from JNU under the Centre for the Study of Social Systems. She later pursued another PhD in Folklore from Gauhati University.

Behal’s life changed when she started working with academician and political scientist Vina Mazumdar in 1980 at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies (CWDS) in Delhi. Mazumdar headed the institute and had also co-authored the first book on the state of Indian women post-independence in 1974, named Towards Equality: Report of the Committee on the Status of Women in India. It was she who suggested Behal to do a thorough research on the state of women in northeastern states, which in turn opened the doors to many reforms that Behal would work towards in the coming years.

In 1984, while she was researching for CWDS in a village in Mainpuri district of Uttar Pradesh, Behal was shocked to see the oppressive condition of not just women but also men because of casteism. The northeastern states, she says, with higher presence of tribes who have their own set of norms and mores was less plagued by this ancient social evil. The area also had existing co-operatives and the people were welcoming of change, believes Behal.

On returning to Assam, she started working at a school in Tezpur, which granted her funds to work with rural women weavers. “When I chose the Northeast, I knew half my battle was won,” she says.

By 1995, she wanted to work beyond the confines of Tezpur Samiti, with other northeastern states such as Nagaland, Mizoram and Manipur. She started the North East Network (NEN) the same year.

Network begins

“We don’t have to fight men, we need to fight the concept of patriarchy,” she says about the founding idea of NEN. The organisation has been active in the scene for 24 years now, working for various developmental goals such as ecologically responsible practices, improving womens’ healthcare and better agricultural practices.

Around the same time, in 1995, Behal got a special opportunity through the MacArthur Fellowship and chose to work in Nagaland for the next three years. At the end of that, in 1998, she started a branch of NEN in Chizami, a village in Nagaland’s Phek district.

After working there for a decade, Behal helped the weavers of the village form a co-operative under NEN’s Nagaland branch, to help them get better pay for their work. It worked well and the initiative nearly doubled their wages. “On an average, a weaver’s pay went up from Rs.40 to Rs.110,” Behal says. Beginning with shawls, they have now diversified into clothes, bags and table clothes, after she onboarded her son’s NIFT graduate friend on to the project. Today, the co-operative, which started with six to seven weavers, has around 600 on their team.

For NEN, however, the longstanding battle in Nagaland has been getting women to contest and win in elections. Till date, not a single woman has been elected into the state assembly. “We have been trying to educate people, especially women, of their governance rights through seminars and activities. The progress is gradual, but we are getting positive responses,” explains Behal.

But tireless work yields results, as the network found out through its more recent experience in Assam, three years ago. Behal had asked women representatives from villages to conduct a survey on instances of domestic violence across rural Assam. These women were trained in counselling and researching by NEN. After the findings of the survey came out, with shockingly high numbers of such instances – the NCRB data of 2016 records 3,378 victims of sexual harassment in Assam – NEN managed to raise funds from the Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives.

They interviewed thousands of women across eight districts, before building four counseling centres in different districts. “We want these centres to be of utmost quality. So we are keeping the numbers low for better functioning,” Behal explains. The centres are run by the women who had done the initial research. Adolescents also participate in games through which their awareness about domestic violence is raised.

Support System

While she comes across as a tough woman always on-the-go, working across states with numerous communities and living life on her own terms, Behal confesses to being quite an indulgent mother. “Not that I wanted to spoil my children, but I hardly got to spend time with them,” she says, this time softening her otherwise steady voice. When she is not travelling, most of her days are spent in office, accompanied by her dogs.

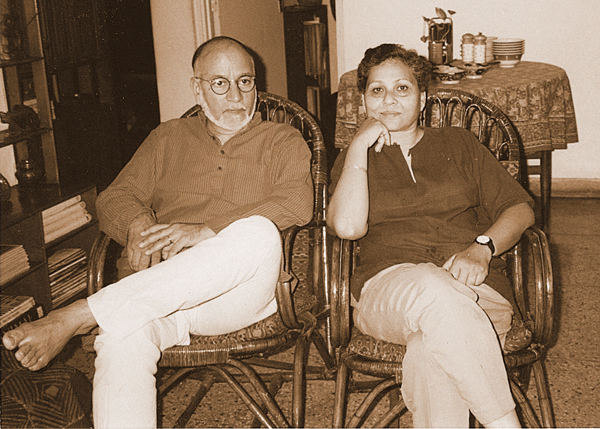

Her son and daughter grew up watching their mother fix bulbs and making wooden boxes outside their house. Behal’s husband Rana, whom she met during her graduation days in Delhi and married in 1977, has supported her through thick and thin. “He has always encouraged my work. Knowing that I am not great a cook, he would cook the meals on most days. We would take turns taking care of our children.” Rana is a retired college professor, presently staying in Germany and writing a book. “He is just like me, always on the go. But my family has been very understanding of my needs,” she laughs. In their younger days, Behal and Rana loved riding on their motorcycle across Assam.

At 67, Behal’s parents are no more. But she has definitely lived up to her mother’s teachings. When a 15-year-old Behal wasn’t ready to attend a puja, her mother told her that it was fine, adding, “doing good to others is the biggest dharma”.