Sex, life and stereotypes – Meet the women who are “doing the nasty”

From sanitation to sexuality, menstruation to lingerie, meet the Indian women who took on age-old taboos and just “minded their business!”

The writing has been on the wall for centuries. It’s what the female devotees sculpted on the facades of myriad Indian temples have been trying to convey to us through their suggestive eyes and erotically charged stance, and it’s echoed by the feisty women change makers steering the social order to align with the natural order – that the lofty ideals we hold our women up to, of being ‘pure,’ ‘chaste’ and ‘dignified,’ go against nature. In fact, our very idea of what it means to be ‘pure’ and what disqualifies one from being so is limited, and one that has kept them away from far too many occupations – be it menstrual awareness, women’s sexuality, sanitation, ironically lingerie even – for too long. But more and more women today are getting down to breaking an age-old stereotype that women can, indeed, get their hands ‘dirty.’

BJP’s Bharati Lavekar may have recently been christened the ‘Padwoman’ of India, but not before a Bollywood megastar reclaimed this title and hulled it of its stigma by boisterously brandishing the unspeakable word and object, ad nauseam, into the faces and sensibilities of Indian cinema-goers.

BJP’s Bharati Lavekar may have recently been christened the ‘Padwoman’ of India, but not before a Bollywood megastar reclaimed this title and hulled it of its stigma by boisterously brandishing the unspeakable word and object, ad nauseam, into the faces and sensibilities of Indian cinema-goers.

The incumbent MLA for Mumbai’s Versova area has been working tirelessly on the ground for nearly two decades to erase taboos surrounding menstruation long before she was elected into power in May 2014 – and long before Akshay Kumar made it cool. Through her NGO, Tee Foundation, she has been conducting awareness drives. She recently set up India’s first ‘digital sanitary napkin bank,’ in May 2017 wherein one could donate money or arrange to donate the sanitary pads directly, to women and girls who do not have the means to access them.

Lavekar’s passion project for her term, is to see every school in her constituency have a pad vending machine. But when she would visit schools helmed by male principals to campaign for menstrual hygiene, at first, they would insist that the boys be ushered out of the classroom for the seminar – but Lavekar stood her ground and not only ordered for the boys to stay, but for all the male staff to attend the presentations as well. “There were a lot of people who would look away embarrassedly when I would ask to discuss healthy menstrual practices. But after the seminars, they would always have a change of heart, and come and tell me that their eyes have been opened,” she tells us. While they collect and distribute nearly 1,10,000 pads per month through the Digital Sanitary Napkin Bank, the “Padwoman” has managed to bring 53 schools under her wings across Mumbai and Thane, where she has not only installed pad vending machines, but also where she and her NGO regularly conduct menstrual hygiene seminars and pad distribution drives in order to drive the usage of sanitary pads over other unsanitary materials such as cloth.

For Richa Kar and Sheela Kochouseph Chittilappilly who wanted to start a lingerie business, starting up wasn’t as simple – considerably more thought went into building the company against a conservative Indian backdrop, and the impact they created was by design, literally and figuratively. Kochouseph pivoted from being a traditional salwar kameez manufacturing company to lingerie manufacturing because the latter lacked players in Kerala that paid heed to design while giving the industry the dignity it deserves. Since the garments set up failed to take off anyway – Kochouseph turned her sights to this lucrative, unaddressed gap in 2000. “You couldn’t say the words ‘bra’ and panties’ in public, especially in Kerala where women stay in the fringes. Many asked me “didn’t you find anything other than this dirty business?” But it was all men who were in the manufacturing field of lingerie, and I wondered how they knew what a woman needs. The prevailing ads and products were indeed very primitive that literally made the lingerie business a dirty one, so here was my golden chance to contribute to bring the lingerie business respect and appreciation through my own brand, V-Star,” she recounts.

For Richa Kar and Sheela Kochouseph Chittilappilly who wanted to start a lingerie business, starting up wasn’t as simple – considerably more thought went into building the company against a conservative Indian backdrop, and the impact they created was by design, literally and figuratively. Kochouseph pivoted from being a traditional salwar kameez manufacturing company to lingerie manufacturing because the latter lacked players in Kerala that paid heed to design while giving the industry the dignity it deserves. Since the garments set up failed to take off anyway – Kochouseph turned her sights to this lucrative, unaddressed gap in 2000. “You couldn’t say the words ‘bra’ and panties’ in public, especially in Kerala where women stay in the fringes. Many asked me “didn’t you find anything other than this dirty business?” But it was all men who were in the manufacturing field of lingerie, and I wondered how they knew what a woman needs. The prevailing ads and products were indeed very primitive that literally made the lingerie business a dirty one, so here was my golden chance to contribute to bring the lingerie business respect and appreciation through my own brand, V-Star,” she recounts.

Sheela embarked on this mission by hiring a professional South American model to sport their novel designs. “When I saw her walking around in her lingerie comfortably with just a shawl around her, I thought to myself, “okay, this is not ‘dirty’ at all,” she tells us.

However, getting these photographs off the road – and on to the hoardings, that is – was a whole other ballgame. “Magazines turned down my print ads, and I was feeling very confused about how to market them. Finally, I decided to put up hoardings – but that met with protests from temples, churches, mosques, colleges, schools, and police even. But I was a fighter. I strove to change the perception of lingerie through the products itself, as well as the packaging, the marketing and presentation. I realized that the social stigma was slowly passing and we got more acceptance with the passing of time. Today, if you flip the pages of any of these magazines, you will find one lingerie ad every five pages. Today, V-Star is the most selling innerwear brand in Kerala, with 14 exclusive stores across Kerala and several more in the works,” she states. The brand currently employs over 3000, and their turnover surged north of Rs. 100 crores last fiscal. With 45 distributors and 4,500 dealers in South India alone, about 15 per cent of their business comes from exports to the Middle East.

While the challenges for Chittilappilly only surfaced at the marketing stage, for Richa Kar, the founder of Zivame, one of India’s first online lingerie marketplaces, everything – right from procuring the unconditional blessings of her family to procuring an office space to kicking off operations – was a stigma-laden experience. Kar recounts how her own family was skittish, initially, when it came to holding conversations about what she did for a living, with their relatives and friends.

When she set out to rent her first office space, she was to share the workplace with a few classmates from BITS Pilani, who were setting up a social sector consulting firm. “While that sounded decent to the landlord, when he asked me, I wondered if I should tell him lingerie. If he then asked for more details, I would have to explain it to him. And will I then miss out on the place?” she had said, in an earlier interview with us. Realising how much was at stake, she decided to pick her battles, and play it safe with this one by introducing her brand as an ‘apparel company’ – much to the amusement of her batchmates.

She couldn’t skirt the moral lens of payment gateway companies with this clever trick, however, as her product’s description was explicitly ‘lingerie and accessories,’ which resulted in long delays to secure the required permissions. But, in Kar’s words, “You have to get your hands ‘dirty’ if it is for something close to your heart.”

Even as Kar stepped down from an operational role and moved to a directorial role earlier this year and a couple of pivots in the business model, Zivame hopes regain some lost ground with its offline push. Having raised $46.7 million in funding so far and a revenue of #53 crore in FY17, they diversified to build an offline presence, setting up 26 stores in the past year and a half. The plan is to take the number of stores to 100 by FY19.

The stakes only get that much higher when what you are championing is not an abstract issue, but something that also directly impacts your own life – like the baffling dearth of awareness in people about women’s sexuality, their repeated denial of your sexual agency, not to mention their overly simplistic categorisation of reserved women as prudish and forthcoming ones as promiscuous.

Sreemoyee Piu Kundu, a senior lifestyle and women’s issues journalist was christened ‘the queen of Indian erotica,’ after she wrote a “full-fledged erotica,” Sita’s Curse. “I find the epithet most flattering and accept it graciously as a compliment,” she says.

Sreemoyee Piu Kundu, a senior lifestyle and women’s issues journalist was christened ‘the queen of Indian erotica,’ after she wrote a “full-fledged erotica,” Sita’s Curse. “I find the epithet most flattering and accept it graciously as a compliment,” she says.

The book was released in May 2014, the exact month when the incumbents, BJP, came to power. It received widespread media coverage and was welcomed by a ten-city launch where it attained glowing reviews, from both women and men, for treading on a terrain most writers and publishers shy away from – the sexual desires of an average, middle class, Gujarati housewife, no less. But the journey to that juncture was a trundle, for when she was pitching the book to publishers, some big names asked her to change the age and socio-economic status of the protagonist. “They thought, who will want to read about the sexual unbridling of a 39-year-old, Gujarati housewife heroine, Mrs. Meera Patel, who is matured and married rather than being a rich, virginal city slicker. They basically wanted to create a desi 50 Shades of Grey at best, but I refused to change a word. And the rest was history,” she states.

Even as people lauded her voice in professional settings, her work had a starkly different effect on her personal life. “The men I meet often perceive me as promiscuous since I wrote erotica, which I feel is a sign of how sexually depraved and regressive their own conditioning has been. I think it’s very hard for Indian men to accept a woman who is very confident of her body and mind and at the same time, treats them like a temple!” she quips. This was Sreemoyee’s second book, and has authored four books in total – the others being Faraway Music, You’ve Got the Wrong Girl and most recently, Status Single. Status Single was a labour of love and almost autobiographical for Sreemoyee, for it unveils the taboos surrounding being an older, single woman in contemporary India. Up next is a straight up memoir, titled Bad Blood, and perhaps a book on Indian men and how they are victims of the patriarchy too, called #mentoo.

While various industries are not considered dignified enough for women to partake in, the equation is further complicated when the layer of caste and class is added to an already unsuitable gender identity for a line of work. So, when Neha Bagoria, the scion of a Rajasthani Rajput family, decided to quit a thriving corporate career to work in sanitation – men’s sanitation, no less – her family was mortified by her choice of work. Bagoria was working with an IT major when she realised she wanted her prowess to be harnessed towards making Indian sanitation technologies more innovative and efficient. She created EcoTrapIn, a small plug-and-play device that would make men’s urinals waterless and odourless.

“When I left my corporate career, it was with the sole purpose of contributing directly to society. Initially, my family was upset with me quitting my career to work in sanitation. It was very difficult for them to understand what I do. They would comment “Is this toilet work what you left your career for?” “How do we tell relatives what you are into now?” “You wasted all your educational degrees to do this!””

But when her efforts aligned with recognition, and coverage flooded in to applaud her feisty strides– Bagoria started to find not only acceptance, but also support from the same family that shunned her. “The support from the media and corporate ecosystem made it easier for me to explain why I did what I did. Now my family is a strong source of support,” she tells us. The Department of Science of Technology, Government of India supported and funded the latest version of her suite of products – ‘EcoTrapInXtra waterless urinal’ – in 2017, which got them much exposure and awards nationally and internationally. “Our revenues have grown by 70 percent year on year so far, and we expect to clock a 300 percent rise revenue in the next two years,” she says.

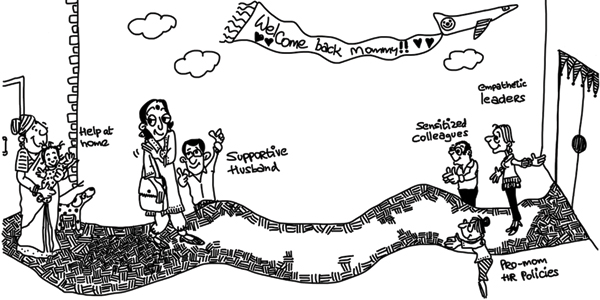

Then again, Chittilappilly points out that for women, any form of professional work is considered a “dirty business” anyway, as women from “good families” do not go out and work, but look after the household. So, when every desire is met with stiff resistance every step of the way, look inward – if you have found your purpose, know that your goals are noble and your conscience clear, take the naysayers head on and relentlessly champion your cause.