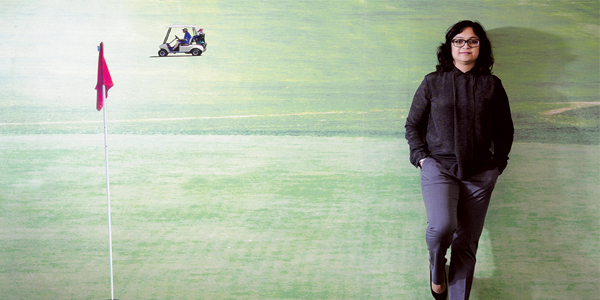

From dropping out of school for marriage, to resurrecting a dying company into a Rs.20-billion empire: Meet Kalpana Saroj

Married against her will and abused, Kalpana Saroj was branded a slave till she decided to be her own master and build a shimmering metal empire

She may have been sadistically abused by her in-laws for minuscule mistakes in domestic chores when she was all of 12; but she returned to the very city where her story soured, and conquered everything from its streets to its skyscrapers. She may have lost a sister for a few thousand rupees, but saved a thousand more lives, by granting them financial support, livelihood, and most importantly, hope. She even waged a war against the goondas deadset on assassinating the gutsy Dalit woman entering their “turf”.

In this surreal tale, Kalpana Saroj defies death, child-marriage and an abusive childhood, survives suicide and supaari, for she was “destined” to meet the worker-owners of the sick Kamani Tubes and resurrect it into a Rs.20-billion empire.

In this surreal tale, Kalpana Saroj defies death, child-marriage and an abusive childhood, survives suicide and supaari, for she was “destined” to meet the worker-owners of the sick Kamani Tubes and resurrect it into a Rs.20-billion empire.

Born to a police constable, Saroj hails from Roperkheda, a village 8 km from Akola. She studied up to the seventh grade, only because her father was adamant that she must at least be a ‘matriculate.’ “In our samaj (community) — girls weren’t allowed to go to school. Since I was a Dalit Buddhist, there was even more resistance. My own family would say, “Usko chulha chakki hi chalani hai (she has to work in the kitchen),” she says.

Proposals, however, flooded in when she was ten. Her mother’s older brother, a domineering presence in the family owing to his wealth, said, “Having an unmarried daughter in the house is like stashing a vial of poison.” Saroj was 12 when she was ordered to honour a proposal from Mumbai. Enamoured by the prospect of living in the big city, her family overlooked the fact that the boy’s family lived in a slum and that to them, daughter-in-laws were slaves.

“The slum was filthy and lacked amenities. I didn’t want to be married in the first place, and I especially hated this living situation and I would cry myself to sleep every night. What’s worse, they were like animals. They made me cook for a family of nearly ten, wash all their clothes. And for minor mistakes — such as too much salt in the food, not getting a stain out — they would just grab my hair, slam me against the wall and brutally beat me up,” Saroj recounts.

Six months later, her father came to visit. He saw his once chirpy daughter in matted hair and torn clothes, falling at his feet, and he immediately decided to take her back. The entire slum witnessed the altercation — for her in-laws had declared, “she was married here and she will die here” — as he escorted her away from that life, never to return again.

They returned to Akola the very next morning, and her father implored her to put the past behind her, and re-join school. “The way everyone looked at me, however, had changed. My own friends taunted me — leaving one’s husband was considered the ultimate sin. I couldn’t shake off the trauma of getting beaten up and shouted at, so, ultimately, I decided to take my own life. There was nothing left to live for,” she says. Life came full circle in a most diabolical way, for the same unwed girl who was considered a vial of poison, now gulped down three. But thankfully, her aunt walked in just in time and promptly took her to the hospital.

She regained consciousness after 24 gruelling hours, but what really marked the beginning of her second shot at life was her family’s reaction. “Nobody cared that I was miserable — they could only think about how my attempted suicide brought them shame. I understood then that no one in this world truly cares about me, so I must not abandon myself. I must live, and only for myself,” she says.

Her first step was to make something of herself. She applied to become a nurse, and even a police officer, but each of them required tenth grade certification.

Grasping at straws in 1975, an uncle living in one of Dadar’s slums became her lifeline. It was decided that she will move in with him, but concerned about her safety, he in turn asked a Gujarati family he knew in the railway quarters — where he sold papads — to take her in. They reassured him, “Until now, we had three daughters, now we’ll have four!”

She landed a job at a textile mill in Lower Parel as a tailor, but when she entered the huge, intimidating unit with rows of machines manned by people with their heads down, working almost robotically, she froze. So, she was demoted to clear up the threads that other tailors would shed while stitching, for a pittance of Rs.60 a month.

In a month, she adapted and asked the supervisor for a second shot at the machines, which she was granted. Earning Rs.250 for the first time, she insisted that her Mumbai family have it, but when she left for work, they quietly tucked it back into her clunky aluminium suitcase.

She had just settled into a routine when distressing news came from Akola. Her father lost his job because of “bureaucratic foul play”, and turned to alcoholism while her mother was seeking work as domestic help. Saroj then put her foot down and ordered them to move to Mumbai, too.

They rented a house in Kalyan for Rs.40 a month. Reunited, they were self-sufficient, but this state of contentment was short-lived. Her younger sister fell ill. The family needed a mere Rs.2,000 to treat her, but they could barely afford two square meals.

She died in Saroj’s arms.

“She kept saying, ‘Didi, I don’t want to die’,” says Saroj, tears welling up in her eyes, even forty years hence. “I learnt how much value money holds in this world,” she says.

Saroj’s purpose in life changed overnight — she was now intent on earning enough money and helping those in despair.

Now on a mission, she chanced upon a government scheme that handed out entrepreneurial loans between Rs.5,000 and Rs.500,000 to women. Nearly two years later, in 1984, she procured a Rs.50,000 loan. She started a furniture business and began earning Rs.1,000 a day. In two more years, she had paid it off.

While their living situation improved, she was always cognizant of the lakhs around her, in the same predicament of unemployment despite every effort. So, she promptly established an NGO Sushikshit Berozgaar Yuvak Sangathna in 1985, to demystify government schemes and documentation through periodic workshops and loan-application drives, often graced by top banking officials, police officers and local politicians. Loans worth almost Rs.40 million were disbursed — and the beneficiaries opened salons, idol-making units, boutiques, and such.

Because of her relentless good work, she earned the epithet tai (‘older sister’ in Marathi). A man, in dire need of money, thus turned to her to make a distress sale of his 2.5 acre plot of land in Kalyan, at Rs. 250,000, merely a fifth of its actual value, in 1995. Borrowing some money and throwing in her savings, she gathered Rs. 100,000, made a down payment and took it off his hands but was in for a rude shock later. The additional commissioner informed her that the plot was a landmine of litigations — and the land ceiling laws dictated that it could only be used for farming. Only the Collector could lift the ceiling on it, but he wouldn’t give her the time of day. But Saroj’s life-savings were at stake.

For about two and a half years, she chased him and honoured every additional date he slapped onto the process, perfected the paperwork, and she ultimately received her clearance. In the process, she came to be known as a litigation expert. The plot’s value shot up to Rs.5 million, but with a clear deed, the land and builder mafia of Mumbai swooped in on it.

She had identified a business partner — Anil Hotchandani, a Sindhi builder — who agreed to foot the cost since Saroj provided the land, on the condition that he pocket 65% of the profits. Saroj, in turn, insisted on developing it under her banner, Kalpana Builders and Developers.

When the goondas saw that she was not backing down, they ordered a hit on her. “They couldn’t stand the thought of a woman — and a Dalit woman, no less — becoming a builder in their ‘turf’,” says Saroj.

But her work with the dispossessed paid off — a member of the hit squad, who revered her for helping his family through a rough patch, promptly warned her of the gang’s intentions. The police intervened and the operation was foiled. The Commissioner advised her to hire security. But the ever-independent Saroj applied for a revolver licence instead. “It was granted within 24 hours,” she laughs.

The building — Kohinoor Plaza — was constructed in 1999, and earned her Rs.40-45 million in profit. She invested some of it in Sai Krupa Sakhar Karkhana, a sugar mill in Deodaithan village. In fact, Hotchandani and Saroj went on to develop a few more projects together, mainly residential apartments in Kalyan and Ulhasnagar, such as Simran Park Apartments Ulhasnagar.

By now, tales of tai’s spirit became legends. That’s why the Kamani Tubes’ labour force sought her out, in 2000. The company, started by Ramjibhai Kamani, a former freedom-fighter who both Nehru and Gandhi regarded as a close aide, was on the verge of closing down. The Kamani empire — Kamani Tubes, Kamani Engineering and Kamani Metal — had shone bright back in its day. But, after Ramjibhai’s death in 1965, differences cropped up among the sons and company became collateral damage.

The workers unionised, stormed the Supreme Court and made a historic demand — that the ownership be transferred to the entire workforce, as the promoters had failed them, which was granted in a landmark judgment.

While they sustained for ten years till 1997, with three thousand owners, the management was sporadic, and self-serving union leaders plundered the treasury. The workers caught on, and seceded to form another union, at loggerheads with the first. Meanwhile, stakeholders, such as the government agencies and banks that had showered them with financial backing in the form of loans and credit when the ownership was first transferred to the workers, now forbade its operations. They went to the extent of cutting off the electric supply, to mitigate further losses.

IDBI assessed the total liabilities, and Saroj had her work cut out for her: a debt of Rs.1.16 billion, and 140 litigation cases against the worker-owners for defaulting on payments, and two unions. More notably, employees who had once been showered with generous bonuses were now begging at bus stops. The company became the prime case study that inspired the Sick Industrial Companies Act, or SICA.

The court ruled that the only way to prevent the company from being liquidated is by bringing in a new promoter. In 2000, the workers approached Saroj, asking her to take over as the company’s president. Her advisors termed it a suicide mission. “But all I thought about was the plight of the workers,” she says.

She resumed the monthly wage cycles of the workers, ran an analysis of their debt, and realised that it largely constituted penalties and interest. So, in 2006, she decided to approach the then finance minister who called an all-heads meeting with the chairpersons of banks including Dena Bank, Canara Bank and Bank of India. She reasoned with them — if the company goes into liquidation, no one gets a single penny, but if the penalties are waived off, the lenders will at least recover their principal amounts. This resonated with them — the banking heads not only signed away the interest, but also agreed to deduct 25 per cent from the principal, if the money was paid back within a year — and Saroj delivered.

In the same year, she was appointed chairperson of the company, and the court transferred ownership of Kamani Tubes to her. In 2011, they left the ‘sick’ zone.

In the year 2013, she was awarded the Padma Shri for her contributions to Trade and Industry, for valorously taking on a failing business. In fact, the promoters, who had been granted time until 2011 to clear the back-wages, managed to disburse them in 2009 itself, within a few months. And it was at that grand ceremony, where the workers were awarded their dues — Rs.80 million — where Home Minister R R Patil said, “It was destiny that sent all of you (workers) to Kalpana Saroj.”