The mover

Autoplant founder Uma Rajan knows the secret of making timely deliveries is to keep going, however the road winds

When a person is thrown in at the deep end of a pool, they can either swim or sink. Uma Rajan swam, and swam hard, every time life tried to keep her down. Take for instance her stint with J Walter Thompson (JWT) in Bengaluru. Uma was only 29 when she was given the daunting job of re-launching HUL’s tea brand Red Label. She had just returned from the US in 1992 and had taken up a job in the client servicing department. A few months into the job and her senior – the account director – resigned, and she had to step into his shoes.

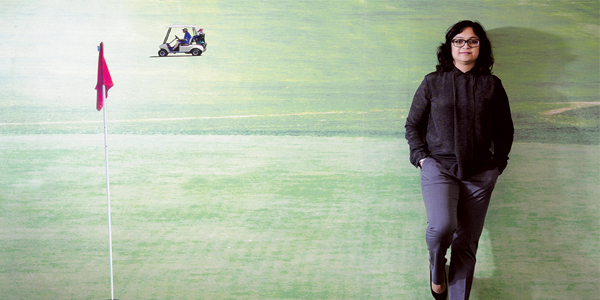

She had no prior experience in this, but she dove right in. After two years of number crunching, locating markets and finding the best ad spots, the re-launch was finally executed in 1994. It was a hugely successful one, though she was miles away from her comfort zone. “The launch of one of the largest brands in the world – comprising a new logo – gave me a huge serotonin rush. It was a steep learning curve. But, those 2.5 years marked a turning point in my life. It helped me get over my fear of managing a business,” recalls Uma, as she settles down for a chat at her office in Navi Mumbai. Her classic corporate attire – a crisp white top with black trousers – and confident gait speaks of the long way she has come, since then.

She had no prior experience in this, but she dove right in. After two years of number crunching, locating markets and finding the best ad spots, the re-launch was finally executed in 1994. It was a hugely successful one, though she was miles away from her comfort zone. “The launch of one of the largest brands in the world – comprising a new logo – gave me a huge serotonin rush. It was a steep learning curve. But, those 2.5 years marked a turning point in my life. It helped me get over my fear of managing a business,” recalls Uma, as she settles down for a chat at her office in Navi Mumbai. Her classic corporate attire – a crisp white top with black trousers – and confident gait speaks of the long way she has come, since then.

Today, she is the co-founder and senior partner of Mumbai-based Autoplant India, an IOT-enabled logistics firm that has offices in Delhi, Bengaluru, Kolkata and Mumbai. Founded in 2011, it employs 300 people and boasts of a marquee client list of over 60 corporates across manufacturing, cement, retail and FMCG sectors. Their names include Coca-Cola, Vedanta, UltraTech Cement, Havmore Ice cream and Asian Paints. Till date, the company has automated over 60 plants, tagged 300,000 trucks and installed 50,000 GPS trackers. In FY19, it clocked an annual turnover of Rs.300 million.

Tracing the roots

Uma comes from a family of academicians – her father was a scientist working with the government’s atomic energy division and was closely involved with India’s first nuclear test, codenamed Smiling Buddha, while her mother holds a PhD in plasma physics and computer science. Uma pursued a degree in economics and mathematics at Nizam’s College in Hyderabad, followed by Masters in planning and accounting from Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai. In the early 80s, she joined Centre for Organisation Development in Hyderabad as a PhD student.

She moved to the US with her husband, Naren Rajan, while she was still working on her research paper. However, between looking after two children and adjusting to a new country, Uma could not manage to complete it. But, she says, “I was determined to continue working after we moved back to India,” she says. Sure enough, she did take up the job at JWT as soon as she returned to India in 1992, and continued working there for three years.

The family had to move once more, from Bengaluru to Coimbatore, where her husband’s parents who run the prestigious PSG Sons and Charities are from. Here, Naren had started a real estate firm called Tristar Group of Companies, and she decided to help him scale it up. She was responsible for project planning and completion, but it wasn’t a bed for roses. In 1998, a series of 12 bombings killed 58 people in the city, and people did not want to put their money in Coimbatore. “Our sales came to a standstill, and I had to sell my house to put money into the business,” recalls Uma.

A regular person would have lost their spirit from the constant pushbacks. But Uma, after seeing the execution of over 200 apartments, just learnt something new about herself: “I did not want to join a company that was doing well and become a cog in the wheel. What I really wanted was to join a start-up or a company that is not been doing well, and turn it around.” Alongside Tristar, she began working as a part-time professor of finance at PSG College of Management and as a volunteer for Round Table India. “I tell my kids that it is not all about you. It is important to help people who do not have access to the same resources that you have,” she says.

When her daughter began her studies in the US, Uma began shuttling between two countries, and that is when she joined a non-profit firm called AidMatrix Foundation, set up under the i2 Technologies — a leading supply-chain company. The foundation would get in touch with companies such as Kellogg’s in the US, request them to contribute whatever was their excess and then pass that on to people who needed them. The company partnered with non-profits across the world, including Counterpart International and Women for Women, and Uma helped strategise and execute the projects.

After five years here, Uma moved to the New York-based PE firm Seven Hills Partners in 2007. She was to make investment decisions for entertainment, real-estate and technology companies based out of India. During this time, she came across a logistics start-up Novire, which was simply putting GPS trackers on trucks, and realised that there is more that this company could do. “Despite good supply chains, corporates do not know when their raw material would come or when the finished product would be delivered. I thought we could solve that problem,” she says. Uma bought out Novire for Rs.5 million and that was the starting point for what is today Autoplant. She then approached Hiten Varia, who she had met while working with AidMatrix. “During that time, i2 was getting acquired by JDA Software and he was planning to move out,” she says. Varia inturn got Venky Nayar, Suresh Sachdev and Prabhu Natarajan on board, all former i2 employees with vast experience in supply chain management and solutions.

The founders collectively invested about Rs.6 million in starting the company and developing a strong tech-backed platform using GPS, RFID, IoT and ML, to bring down cost and improve efficiency of transportation. Founded in 2011, their Mumbai-based company is an IoT-enabled logistics management firm, which allows a company to track the movement of its materials and products end-to-end. That is, a company can see raw material coming in and leaving as a finished product and also follow it all the way until it is delivered to the customer. All this at reduced costs and improved time efficiencies.

Even in 2010, before Autoplant was founded, the team had begun scouting for big clients. They approached UltraTech Cement, which they knew had trouble with transporters and logistics. After a successful pilot, the company signed on as a client. While Uma’s partner had pitched to UltraTech, she presented to L&T in the same year. L&T was moving goods from Chennai to Pokhran and wanted it monitored because of pilferage on the way. “This was the first time we were using GPS as a supply-chain tool. We were offering to integrate the entire logistic process with their ERP, Tally and their other internal software,” recalls Uma. L&T’s senior management came onboard immediately, and the project began two months later.

Today, Autoplant’s services are neatly divided into four verticals. The first is ‘Collaboration’, which brings shippers and transporters onto the same platform. The second is ‘In-Plant’ platform that enables clients to organise logistics more effectively and optimise turnaround time. The third is ‘En-Route’ tracking system that closely monitors vehicular movement, and the last is ‘Last Mile Processing’ that digitises delivery confirmation in real-time. The entire solution is based on a SaaS model. The clients enter into a three-year contract and are charged on the solutions they use for each trip. Uma adds, “We have even automated whole plants.”

She cites their solution for ice-cream maker Cream Bell, which was dealing with problems such as low visibility of storage, distribution and sales of products. Autoplant, with its cold-chain IoT solution, provided a dashboard through which the ice-cream maker could track the carts’ temperature and location. Any anomaly, particularly rise in temperature, would trigger an alarm in the supply chain.

Like any business, Autoplant too has seen its highs and lows, but Uma has never stopped being excited about her job. “The very idea of running a business, managing a team and helping corporate save millions of dollars keeps me pumped,” she says.

Showing Strength

With a strong product and client base, Autoplant has continued to grow at an impressive pace. In 2015, another tragedy struck the Rajan family. Naren succumbed to a biking accident in Madrid. Troubles compounded when, following this mishap in 2015, the family had to deal with court cases and the difficulty of completing pending projects and getting fresh deals at Tristar. “In real estate, a lot of sharks circle you. Fortunately, I have had a supportive family to pull me through,” she says. Uma also credits her business partners for being both patient and appreciative. Her younger daughter Rashmi and son-in-law Gaurav now handle the business.

You don’t see many women in the logistics industry. But Uma says that she has never been treated differently because of her gender. “Knowledge is power,” she says, adding, “Your first 10 opening sentences have to make sense.” She sure seems to have found a stronghold in this industry. The client retention rate at Autoplant has stayed at 96% consistently.

Sure, there have been blips, such as the hit the business took after demonetisation and the rollout of the goods and services tax (GST), or the current slowdown in economic activity. But Uma expects business to pick up in the coming year as they are looking for external investors to take business abroad. To expand business into the Asian markets, the start-up has signed a deal with JDA in November.

Until now, the company has mostly focused on road transportation, but there are plans to delve into waterways and airways, too. Uma has her hands full, dividing time between her business and family commitments. “Every day, my mind keeps busy thinking about what can be done next,” she says. Her ambitions aren’t small or easily met, but when has that ever stopped her.