The visionary behind Kolkata Literature Festival actually helms two other equally iconic businesses: Meet marketing maestro Malavika Banerjee

Sports, saree and literature sit comfortably in Malavika Banerjee’s collection of interests and successful businesses

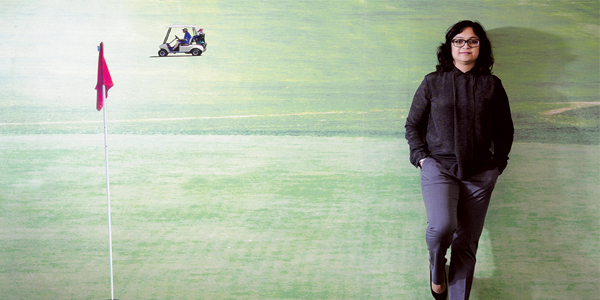

Malavika Banerjee calls her two-storied, renovated mansion a ‘sensory overload’. Red walls adorned with shelves of bags and potlis, wooden cupboards stacked with neatly folded kurtas, dupattas, and quilts in a blend of blues, oranges and yellows. A corner is stacked with brass diyas, homeware and bottles of organic body products. Upstairs, the rooms greet you with an old-world charm — arched walls, shuttered windows and armoires lined with sarees and blouses. That’s Byloom for you at 58B Hindustan Park in Kolkata. Banerjee is one of the partners of this popular saree boutique, but her own career spans across sports, literature and handloom, born out of the sheer love for the city.

Banerjee considers herself a thoroughbred Kolkata girl. Her mother was a teacher and her father, an IAS officer, was also posted here. After finishing her schooling at La Martiniere for Girls, she joined Lady Shri Ram College in Delhi. Later, she moved back to Kolkata for her master’s degree at Jadavpur University. “I was never terribly ambitious. Since it was said that journalism is one of the natural routes taken after an MA in English, I did that too,” she says. Banerjee nabbed a job at The Asian Age within a month of graduating and managed the Kolkata edition for three years till 1998.

Banerjee considers herself a thoroughbred Kolkata girl. Her mother was a teacher and her father, an IAS officer, was also posted here. After finishing her schooling at La Martiniere for Girls, she joined Lady Shri Ram College in Delhi. Later, she moved back to Kolkata for her master’s degree at Jadavpur University. “I was never terribly ambitious. Since it was said that journalism is one of the natural routes taken after an MA in English, I did that too,” she says. Banerjee nabbed a job at The Asian Age within a month of graduating and managed the Kolkata edition for three years till 1998.

Married into a business family, she swore for the first six months to never become a businesswoman or collaborate with her husband or the family. Her husband Jeet Banerjee owned an advertising agency. But the couple was passionate about sports, and her husband encouraged her to merge their skills. She says, “My husband said, ‘Why don’t we start something with your core competency in generating content and my ability to market.’” In 1998, the couple launched sports marketing company, Gameplan Sports.

The company kicked off by offering target articles written by cricketers to various top newspapers. Within two months, Gameplan had bagged their first significant client: former Pakistani cricketer, Wasim Akram. The Pakistan cricket team was touring India in 1998-1999 and to represent the captain of an opposing team was quite the high for the company. “We rode the dotcom boom and the growth of content and sports in India,” says Banerjee.

Over the next five years, the company shot to fame as one of the biggest content providers of sports. Gameplan was soon working with regional newspapers such as Eenadu, Dainik Bhaskar, Sakal, Punjab Kesari and Malayala Manorama. But sports marketing was still at a nascent stage, and this emboldened the couple to explore other fields in the business. The company introduced in-stadia advertising and 3D signage implemented during the 2011 World Cup, Indian Super League in football, the Pro Kabaddi League, and Fédération Internationale de Hockey, among others.

Banerjee says, “Gameplan has always been able to anticipate and ride each wave of innovation in sports in India.” The company, with its 20-member team, today operates in event and player management and presents the Kolkata Literary Meet (KLM) and Tata Steel Chess India, the country’s first international chess tournament. Gameplan has also been collaborating with Royal Stag to present Large Short Films, which includes Sujoy Ghosh’s Ahalya (2015) and Anukul (2017), and Neeraj Pandey’s Ouch (2016). “My heart beats for sports, everything else is done by the head,” says the co-founder and director of the Rs.250 million company.

Weaving beauty

As a student in Delhi, Banerjee noticed that most girls at Lady Shri Ram College wore khadi kurta, jeans or Patiala salwars. In her batch, only one girl wore saree every day. “I realised that this garment — whose beauty we take for granted — is in some jeopardy,” she says. This was in 1990, but she had a hunch that it would possibly meet the same fate as the Japanese kimono. Banerjee had inherited her mother’s fondness for sarees and, at 19, she could tell a Gadwal from a Mangalagiri or a Venkatagiri; or make out an Ikat of Odisha from an Ikat of Gujarat.

In January 2010, Banerjee and her husband bought an old, dilapidated building, with little clue what to do with it — this would later be home to Byloom. When Banerjee had met Bappaditya and Rumi Biswas a year earlier, they were creating beautiful weaves under their brand Bailou out of a little studio.

Bailou, started in 2002, had managed to conserve the balance between beautiful and easy-to-maintain sarees, while also working with over 1,000 handlooms and weavers at the grassroots level. Banerjee says, “At that time, I was a sports marketing agent. It’s the one place you will never see a saree.” But just after she bought the building, Banerjee proposed a collaboration: Bailou’s sarees and Banerjee’s decade-worth marketing experience. In 2011, Byloom was launched as the retail venture to Bailou and, as per latest records, has Rs.120 million in revenue.

Banerjee remembers that she was working closely with cricketers and various sports editors during the 2011 ICC World Cup, when she broke the news of venturing into sarees and handloom. “It was in their incredulous look that I realised that it was a huge leap. In India, we tend to focus on doing one thing well. But in my reality, I was as fond of sports as I was fond of saree,” she says.

Banerjee successfully implemented some marketing ploys, especially when it came to social media. “Something I learned from Gameplan is not to be nostalgic. We are on a technology treadmill,” she says. She took notes of how top designers were using Facebook and Instagram as their platforms of advertising, and managed to mimic the same with Byloom. “We liberated the saree from the pujo ghor (worship room and traditional function) and the biyebari (wedding),” she adds.

It has been especially gratifying for Banerjee to hear 20-somethings come into Byloom and say, “We want to wear a saree” — a significant milestone since her Lady Shri Ram days. Today, Byloom has impressive celebrity following too: Aparna Sen, Kirron Kher, Priyanka Gandhi, Hillary Clinton and even Sonakshi Sinha’s wardrobe in the periodic film Lootera. But that is not what the brand wants to communicate. “Our models are doctors, engineers and students. This is a saree for real women — and what Byloom spun off as,” she adds. Byloom focuses on a mix of silk, cotton, linen, jamdani and ghicha weaves, ranging from Rs.800 to Rs.15,000.

Byloom has now ventured into menswear and children’s wear. Inspired by Sri Lankan concept stores, Byloom also launched a café, Byloom Canteen, within four months of opening its doors to the public. The canteen, too, captures the essence of Kolkata’s foodie spirit with fish and chips, mangshor chop and luchi on the menu.

Literary calling

Banerjee was attending the Jaipur Literature Festival in the January of 2010, when a chance conversation with an attendee inspired her next business venture. The woman confessed that she wasn’t proud of the festival; it did not feel like Jaipur’s festival. It felt more like a tourist’s festival with majority of attendees coming from outside the state.

Banerjee pondered over the grievance and returned to Kolkata with hopes of starting an edition here. It is the city of literature, home to India’s first and only Nobel Laureate for literature, Rabindranath Tagore, home to the first English novel written by an Indian (Rajmohan’s Wife by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay). Banerjee was at the threshold of her 40s and had the urge to do more than sports. So she put her marketing skills to play and created a PowerPoint presentation explaining how to host a literature festival in Kolkata. But the idea was dismissed – she was advised to stay on track with her sports business. Though she dropped the idea, as fate would have, Sujata Sen, then director of British Council East India, found her presentation in September that year and reached out to her few months later. The only problem: she had to host the festival in four months.

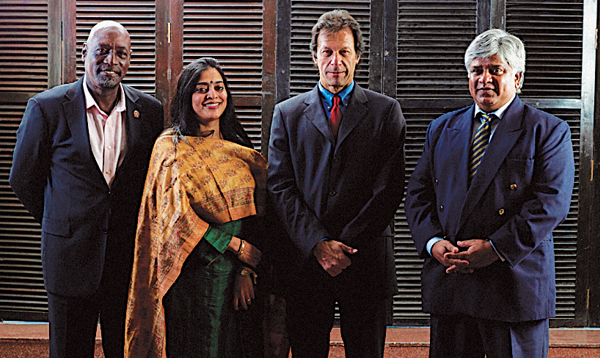

“I didn’t know a single writer; I didn’t know a single publisher. But it was too tempting to say, ‘no’. So I went for it. One thing I’m good at is acting first and thinking later,” she quips. Banerjee reached out to Vikram Seth by her ‘six degrees of separation’ and invited Sunil Gangopadhyay to jointly inaugurate the festival. By then, she had done a lot of work with Pakistani cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan, and invited him to talk about his book. In the first year, KLM needed some showstoppers to make an impact, and they were able to hit the ground running with names such as Amit Chaudhuri, John Keay, Manu Joseph and Rituparno Ghosh.

Over 10,000 book lovers attended the festival and the overwhelming response encouraged Banerjee, as the festival’s director, to shift the annual event from Kolkata Book Fair to Victoria Memorial. The next milestone happened in 2015 when Tata Steel agreed to become the title sponsor of KLM. “Now, the litfest consumes me. I’m always looking out for writers and reading reviews in The Guardian and The New York Times. It’s an endless joy,” says Banerjee. Besides hosting extensive sessions on literature, the festival also promotes cinema and performing arts. In the latest edition, hosted in January 2019, about 45,000 people attended TSKLM.

Gameplan and Tata Steel has since expanded the literary festival to Bhubaneswar in 2016 (Tata Steel Bhubaneswar Literary Meet) and Ranchi in 2017 (Tata Steel Jharkhand Literary Meet).

Learning curve

Banerjee looks at every setback as a stepping stone to something better. During the dotcom boom between 1998 and 2000, for instance, Gameplan had signed on many people and distributed content to various websites. But when things went southwards, they were left with not much work. “The big challenge is not to get sentimental about the way things were but address the change,” she says. Now, she surrounds herself with young people to teach herself technology, social media and even the ‘bewildering world of Netflix’.

A particularly low point was in 2010 when Gameplan was managing former Indian cricket captain MS Dhoni and he sued the firm over an advertising deal that went awry. “That was the time I did not feel like working in sports anymore. So I started looking at other avenues, and that’s how Byloom and the literature festival happened,” she says.

For Byloom too, she remembers the initial days when women would walk into the store every month and ask, what’s new. She says, “I would be baffled. What was I supposed to say? Now I realise that is the very question that keeps brands such as us alive.”

And when it comes to bouncing back after a failure, Banerjee takes notes from the array of sportspersons she has worked with. In 1999, India lost a Test match to Pakistan. When Banerjee met the players the next day, one of them shrugged off the matter as though it was nothing. “I was shocked. But that (nonchalance) is what defines your ability to bounce back. As a sportsman, you see defeat as a norm. I instinctively took that lesson on board,” she says.

She says, “Setbacks stay with you longer, but what you do with them becomes your high point. Now I’m 47, and I see the bigger picture.”