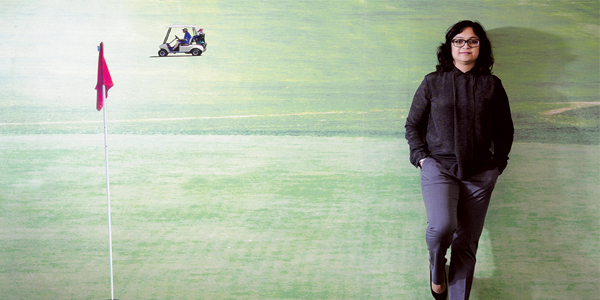

Busy bee

She built a company that is the largest buyer of tribal honey in India. How did Chayaa Nanjappa pip the biggies in the game?

Ranveer Singh’s “Apna time aaega” has come to be quoted often. It is meant to inspire, get people going. But Chayaa Nanjappa has never needed it. With sheer will, a kind heart, and one helluva smile, she has managed to bring better days for herself and about 1,000 tribal farmers.

She is the only child of a Coorgi coffee planter and a school headmistress. Her parents were in their 40s when Nanjappa was born. Quite understandably, they doted on their daughter, who also turned out to be an “above average” student. To expose her to the city life, the Nanjappas sent her to Christ the King Convent — a boarding school in Mysuru.

She is the only child of a Coorgi coffee planter and a school headmistress. Her parents were in their 40s when Nanjappa was born. Quite understandably, they doted on their daughter, who also turned out to be an “above average” student. To expose her to the city life, the Nanjappas sent her to Christ the King Convent — a boarding school in Mysuru.

Start of something new

In 2002, when she turned 30, tragedy struck. She lost her father Paruvangada Nanjappa to a heart attack, and she decided that it was time to set out on her own. She shifted to Bengaluru in search of a job and a life away from the confines of her village. Nanjappa came to be fiercely self-reliant. While browsing through newspaper classifieds for a paying guest room, she spotted an opening at The Chancery, a premier hotel in the city.

Prior to the interview, Nanjappa admits she lacked the confidence to even sign a cheque. Further, the loss of her father put her in one of the lowest phases of her life. However, she powered through. Nanjappa happened to exchange pleasantries with Taposh Chakraborty, the then VP of The Chancery. Despite Nanjappa having no prior experience in the hoteling industry, Chakraborty roped her into the hotel’s ‘Guest Relations’ department. Here she did exceptionally well, even convincing regulars at The Leela to try The Chancery.

Buzzing for business

Four years later, Nanjappa realised she wanted to do more. Her independent spirit guided her to entrepreneurship. Coorg is synonymous with coffee, but she wanted to market the hill district’s honey. As a child, she had seen how the farmers struggled to reach their produce to the marketplace. In the 90s, Thai Sac infection wiped out apiaries in the region. To rebuild that broken industry, she started Nectar Fresh, in November 2007. She had pitched a dart into the dark, but she didn’t want her brand to disappear into obscurity; there were so many honey brands for the taking.

Then, drawing on her previous experience, Nanjappa decided to sell to the hotel industry. It was a smart move. For one, she knew that the retail market was crowded with the biggies such as Dabur and Himalaya. For another, she had friends and ex-colleagues in premier hotels. Nectar Fresh decided to position itself as a boutique player and that meant betting all your chips on quality. Nanjappa wanted to challenge brands such as Beerenberg and Darbo, the then go-to honey brands for top hotels. With the bar set high, in early 2007, Nanjappa headed to Central Bee Research and Training Institute (CBRTI) in Pune to train, and by end of the year, she set up her manufacturing facility in Bengaluru’s Bommanahalli with the help of the Khadi India and Village Industries Board.

She started with five villagers and taught them to operate the honey-making machines. To set up the facility, her mother helped with Rs.1 million, Rs.1 million came in from a bank loan, and Nanjappa sold her jewellery for another Rs.800,000. By the turn of 2008, Nectar Fresh was ready to start shipping and, in two months, it was catering to 100 hotels. By mid-2008, it had Le Meridian as its first big-league client. Back then, a Khadi industry commission-backed brand entering big hotels was unheard of. The same year, ITC got wind of Nanjappa’s venture and became the first FMCG brand to back Nectar Fresh. Today, its Srirangapatna facility packages ITC’s honey.

Nanjappa has bagged many awards, such as the CNBC Women Entrepreneur Award for 2014-15 and the Rotary Mysore Midtown Best Industrial Award 2018. While she has never strayed from her social mission of bettering the lives of farmers, Nanjappa steers clear of calling her enterprise non-profit. It is unapologetically a for-profit venture.

Growing the hive

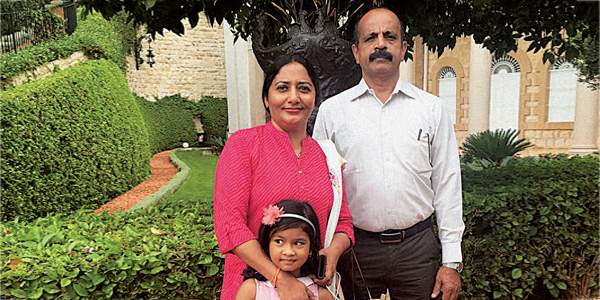

By 2010, Nanjappa knew that she needed a partner. Back in Coorg, her friends introduced her to Kuppanda Rajappa, who hailed from a Coorgi business family and is known to have started one of the first supermarkets in the town. Given his experience in the FMCG game, Rajappa made for the perfect partner. The two hit it off, but there’s more to this partnership.

In the early 90s, Rajappa’s family had sent a marriage proposal to Nanjappa. She had rejected the proposal, but who would have known that fortune would bring the couple together two decades later? Rajappa now handled manufacturing, accounting and quality control, and Nanjappa took care of building the brand’s relations and marketing activities. The duo was keen to scale up. The idea was to build a farm-to-gate facility, which cut down on logistics and brought the brand closer to its producers. In 2014, Nectar Fresh set up its current facility in Srirangapatna, smack-dab by the Bengaluru-Mysuru highway. It’s one of those rare addresses that Google Maps displays with pinpoint accuracy.

Nectar Fresh today makes a varied range of products, including jams from Totapuri mangoes. The fruit farmers were going deeper into debt, unable to sell their produce, when Nanjappa’s company stepped in. Her filter for adding new products to their portfolio is simple: “Would I give it to my daughter, Niyama?” That is her eight year old. Understandably, if it’s good for little Niyama, it’s good for you.

If you think of it, that’s a business lesson right there – focus on quality and the marketing will take care of itself. Nanjappa keeps a zero budget for marketing and advertisements. In fact, Nanjappa and Rajappa are downright media-shy. It saves them time, effort, and money, and also allows them to sell at prices that big brands can’t afford to. “What can take you places in business is ethics, and that’s the only reason that Nectar Fresh is where it is today,” she says.

Sticky days

Nanjappa is proud of building a bona fide “Made in India” brand, but it has come with its own challenges. For one, she has had to push her workers to meet deadlines. “You need to be after them to get work done,” she says. Second, engaging rural women, who have never stepped out of the confines of their home, is difficult. Third, banks only talk big, but deliver little. “SBI offered us loans at 14%! They will sit on a dais and talk about schemes for start-ups and women entrepreneurs, but offer little benefit in reality,” Nanjappa says.

Hurdles notwithstanding, she has built her venture one step at a time. Today, Nectar Fresh supplies to some of the largest retail chains such as Walmart and Spam Hypermarket, while a deal with the Aditya Birla group is in the works. Nanjappa supplies to over 320 hotels, and in addition to the hospitality industry, the brand is also making inroads into ayurveda and pharma. Remember her ambition of dislodging the monopoly of imported brands in the hoteling industry? That’s a box Nanjappa ticked rather quickly. While foreign brands charge Rs.500/kg of jam or fruit preserve, Nectar Fresh manages to price theirs at Rs.130 by saving on ad spends. Nanjappa claims that the brand is expected to grow by 40% as she looks to ramp up production from 700 tonnes to 1300 tonnes by year-end. The brand has reached a stage where shipments from Nectar Fresh leave only on orders with advance payments, she claims.

Next, Nanjappa wants to get into the corporate gifting space. And after that, she hopes to build India’s largest tribal art retail chain, named Jayathu Bharatham. She is in the process of identifying localities and products with the potential to scale up. The idea is to support over 2,000 artisans across the country in the next one year, in addition to the 1,000-plus farmers she supports through Nectar Fresh. Lofty ambitions? Of course. But, she has always chased the big prize.