How Meghna Bhutoria is revolutionising learning for children in India

Armed with nuts, bolts and a coding guide, Meghna Bhutoria is determined to make learning fun

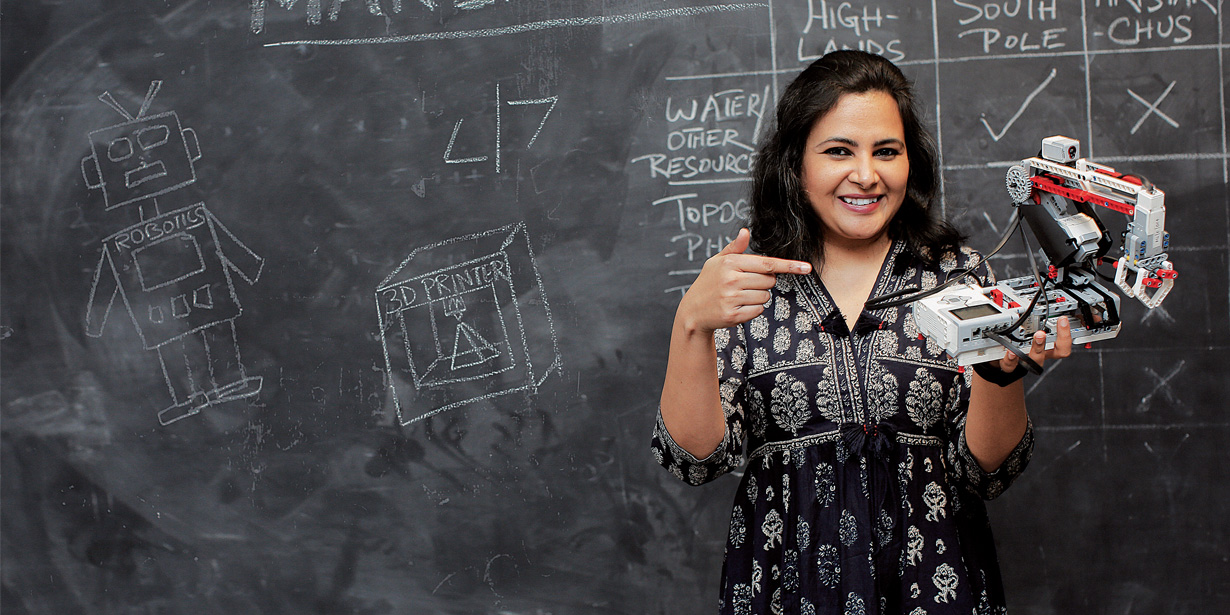

A bewildering sight meets our eye as we step into MakersLoft’s 4,000 sq ft space in Kolkata’s Ballygunge. Kids, across age groups, have neatly divided themselves into clusters, each indulging in a different form of learning. From 3D printing and robotics to coding and carpentry, they are doing it all. More importantly, they are learning these skills not from any textbooks, but with real machines and tools. Precisely how its founder imagined it to be. “I thought of this space as a gym, but for the hands and mind,” says 40-year-old Meghna Bhutoria with a smile, as she takes us through the different sections on the floor. Founded in 2015, MakersLoft is inspired by the Makers Movement in the West, which emphasises learning-through-doing (active learning) in a social environment. Not many had heard of ‘maker’ spaces in India, and Bhutoria, herself an arts and crafts enthusiast, decided to fill the lacuna with her hands-on training start-up.

Since then, MakersLoft has come a long way. Today, it not just has thousands of kids trickling into its institute in Ballygunge every year, but has also tied up with premium educational institutions such as Birla High School, La Martiniere for Boys/Girls, St. Xavier’s Collegiate School and Delhi Public School to provide on-campus labs and train teachers. They have also held two editions of Tinker Fest in Kolkata, a science and art fest which sees participation of students across 70 schools. Buoyed by the response to MakersLoft in the city of joy, Bhutoria is looking at adding more activities and is exploring the franchisee route in other cities.

Since then, MakersLoft has come a long way. Today, it not just has thousands of kids trickling into its institute in Ballygunge every year, but has also tied up with premium educational institutions such as Birla High School, La Martiniere for Boys/Girls, St. Xavier’s Collegiate School and Delhi Public School to provide on-campus labs and train teachers. They have also held two editions of Tinker Fest in Kolkata, a science and art fest which sees participation of students across 70 schools. Buoyed by the response to MakersLoft in the city of joy, Bhutoria is looking at adding more activities and is exploring the franchisee route in other cities.

“We are surrounded by machines, but very few know the science behind them. For instance, every child who rides a bicycle knows it will move forward when you peddle. But if you peddle backwards, the bicycle doesn’t move back. This is because of the ‘ratchet and pawl’ mechanism. Now, in our country, unless you study engineering, you wouldn’t know about this. And this is what we want to change,” says Bhutoria.

Conservative roots

Entrepreneurship though wasn’t Bhutoria’s first choice. Her childhood dream was simple — to be a homemaker. “I grew up in a conservative Marwadi family where all the women were homemakers. So I too wanted to be one, but be better than anyone else because I am very competitive,” quips Bhutoria. She also remembers when she expressed her interest in doing an MBA, and her father had promptly replied, “That is a good idea, but for your brother. You should focus on making better phulkas.”

Despite the conservative family background, she went ahead and completed her BSc degree in Resource Management from Jadavpur University in 1999. She then worked briefly with a start-up in Kolkata before moving to ITC as a Corporate Communication Specialist in 2003.

During her stint at ITC, Bhutoria not just grew professionally, but also personally. “I enjoyed the financial freedom and learnt that men and women are to be treated as equals in every aspect,” she says. But she soon had to move to Pune and then Bengaluru as her then-husband had to move cities. At Bengaluru, Bhutoria took on a challenging role as the Marketing Communication Manager of Silicon Valley-based firm, Cypress Semiconductor. After spending a good five years here, Bhutoria left for an MBA from INSEAD in France in 2010.

“The one-year programme opened up my mind and made me more tolerant of differing views,” says Bhutoria, who secured a job through campus placement with Syngenta, a Swiss-based global company that produces agrochemicals and seeds. As a part of her marketing role, Bhutoria has travelled and lived across regions such as Switzerland, China, Ukraine and the Midwestern US (Nebraska, Minnesota, Ohio, Illinois and Kansas).

However, while her career was at its peak, destiny took its own course. She had to return to India as her mother’s health had started deteriorating suddenly. In January 2015, she moved back lock, stock and barrel. And post her mother’s demise in May, she was ready to start her journey all over again. Except, this time, it was through the entrepreneurial route.

Starting Up

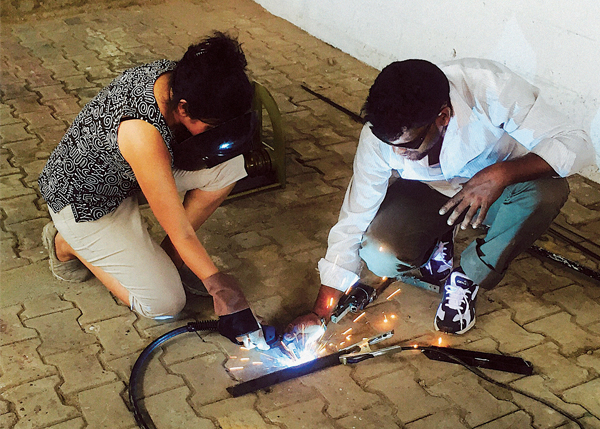

Since school, Bhutoria admits that art and craft have been a secret passion. “Also, during my travels, I had picked up skills such as assembling my furniture, plumbing and architecture. I was looking to create a space where people who have interests like mine can come and create something,” she says.

She began discussing the idea with a couple of friends, who then introduced her to the Maker Movement. After more research, she saw a lucrative business opportunity in the space and founded MakersLoft in August 2015.

“I was looking for a smaller place, but I chose this space as it is centrally located. We then got the tools, such as a 3D printer, Lego, laser cutter, to name a few and opened it up for adults. The initial investment ran into several hundred thousand,” she says, without revealing the exact amount. She also learnt to use every tool and machine kept at MakersLoft.

Six months later, Bhutoria realised that the idea had “bombed”. While people loved the idea of MakersLoft, they did not know what they could come in and do, taking the number of enrollments to less than 100 a month. “I realised that if people haven’t used their hands for over 30 years, then it is less likely they will use it now,” she explains.

At the same time, she observed that the kids accompanying the few adults to MakersLoft were hugely interested in trying out the tools and creating something. This observation led to a pivot for MakersLoft — it decided to target children instead of the adults.

For the kids, Bhutoria began by introducing the concept of learning science, technology, electronics and maths through the use of Lego blocks. By word of mouth, the number of kids coming in to MakersLoft slowly expanded from 20-30 a month to over 300 a month. Parents could enrol their children, ranging from 5-15 years of age, in short modules based on their age group and course type. Bhutoria wanted every child to experience their centre. So, by 2016, they began approaching schools in the city to either train teachers or send their own staff to train children in school.

This, Bhutoria says, required a lot of patience and resilience — almost six to eight months — for schools to see merit in this concept and parents to perceive it beyond an extracurricular activity. “Learning by doing helps kids gain confidence, improves their ability to think logically, makes them more organised, and teaches teamwork and creativity,” she says.

For instance, Bhutoria shares, in 2016, two eight-year-old boys had learnt how to make their own life-size table and chair. “We gave them big saws and taught how to use it. Those kids cut large pieces of ply, learnt how to nail and drill holes and paint. So it took them a few months but when the final product was ready, their and our happiness was palpable,” she says with a grin.

Similarly, MakersLoft has an interesting project called Banana Piano. In this, the bananas become the keys of the piano. “First we make them play the (banana) piano and they look under the table as if it’s magic. But we tell them it’s science, not magic!” she says. Essentially, it is a combination of coding, software and hardware, and kids learn all this in an innovative and interesting manner.

Currently, MakersLoft has expanded the activities and certificate courses it offers to include programming language, Lego STEM, Python, app making, 3D doodling, robotics, wood working, natural dyeing and block printing. They have also opened a similar centre in Alipore, to widen their presence in Kolkata.

Tackling Hurdles

Like any unique concept, MakersLoft too faces its own set of challenges. The first pertains to revenue. The bootstrapped start-up hit profitability in their third year of operations, but revenue is still under Rs.10 million. Another challenge, and perhaps the most important one, is to find the right skill sets. “Teachers typically are from an English or Humanities background. They do not know 3D printing, Lego or robotics. So we started with hiring from a fresh batch of engineers, but they don’t want to be teachers forever, so they tend to leave in a while,” she points out.

With parents and schools gradually waking up to the importance of learning by doing, hiring is a challenge that Bhutoria is confident of overcoming soon. “The pace of change is slow and it takes a lot of patience to fight the same battle day in and out,” she says. For now, her priorities are set straight — to take the concept of MakersLoft to more schools and cities. Because the future is in the hands of the kids, and they need to create it well.