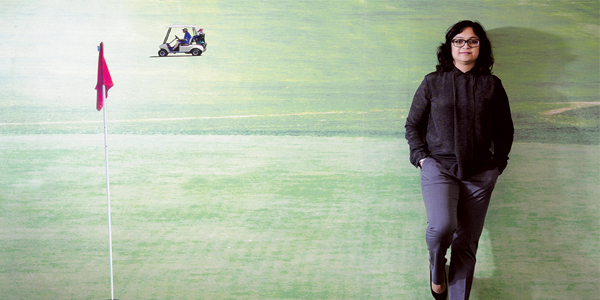

From war-survivor to the “Don of Chinatown,” how Monica Liu turned her life around through her restaurant business

Liu, who owns four successful Chinese restaurants across Kolkata, owes her success to the hardships she has faced while growing up

Among the thousands of prisoners inside the fenced grounds of Rajasthan’s Deoli camp, a nine-year-old girl stood out. Monica Liu’s routine still retained few activities from her pre-confinement days: wake up, bathe her siblings, wash their clothes and feed them. Additionally, her chores now also included standing in the queue for a bowl of rice and mutton that was almost always stale or raw, and fetching water from a faraway tap within the grounds. Over the next five years that she spent in captivity — in not one but three prisons — the routine did not change much. Years later, infected by the urge to start something of her own, she finally broke free of the monotony. Today, Liu owns four successful Chinese restaurants across Kolkata — Kim Ling, Mandarin, Beijing and Tung Fong.

Born Leong Sue Yek (her Chinese birth name) in Kolkata to Chinese immigrant parents, Liu moved around a lot as a child — first to Kalimpong and then Shillong. But long before she became a restaurateur, when Liu was 8, she would help her parents out at their restaurant in Shillong. On days when her mother was busy, one could find Liu in the cashier’s seat. “Sometimes, I miscalculated the money because, at that time, there was no cash register,” recalls the 64-year-old. So, what was her accounting method like? Make 10 columns for the restaurant’s 10 tables, jot down the order amount and strike it out as soon as the customer pays.

Born Leong Sue Yek (her Chinese birth name) in Kolkata to Chinese immigrant parents, Liu moved around a lot as a child — first to Kalimpong and then Shillong. But long before she became a restaurateur, when Liu was 8, she would help her parents out at their restaurant in Shillong. On days when her mother was busy, one could find Liu in the cashier’s seat. “Sometimes, I miscalculated the money because, at that time, there was no cash register,” recalls the 64-year-old. So, what was her accounting method like? Make 10 columns for the restaurant’s 10 tables, jot down the order amount and strike it out as soon as the customer pays.

Being the eldest sibling in her family, the responsibility to manage the restaurant as well as her sister and two brothers, naturally, fell on her. All this, while balancing school too. If anything, Liu explains how this taught her to be self-sufficient from a very young age. “At that time, my parents used to be busy handling their business so that we could have a better living. So, I would have to look after everything else,” she says. But then came the 1962 Sino-Indian War that uprooted not only this young girl and her family, but several other Chinese-origin residents like her.

Train to Deoli

When the police arrived at their door that November, the family couldn’t have guessed that they would not be returning anytime soon. After spending about 15 days in a jail in Shillong, Liu’s family was taken to Guwahati and herded into a train heading for the internment camp in Deoli, Rajasthan.

From Rajasthan’s scorching days to barely edible camp food and mosquito-infested nights spent sleeping outside — Deoli took a toll on Liu’s family, she says. “We were free to move around, but we suffered every day. We didn’t have work, we didn’t have an education. They only gave us food,” she says. That’s when the camp residents took it upon themselves to bring a change. Liu’s family, like many, began planting vegetables inside for farming; collecting frogs at midnight and feeding it to the camp’s chicken to get better eggs; mixing flour with rice to feed more mouths — each alternative a lesson for her.

Eventually, people were released, but Liu’s family was one of the 150 still detained at the camp. They were transferred once more to Nagaon jail in Assam, where they spent another nine months. This is where her family met a young man who persuaded Liu to write a letter to the Home Minister demanding why they were still being held. About 10 days later, they were finally released.

New Beginning

Returning empty-handed to Shillong, the family sought shelter at their friends’ homes. “For a month, my sister and I ate bone soup for both lunch and dinner. But we didn’t complain because at that point of time, we were very thankful that we had a place to stay and food to eat,” Liu says. After about a month, Liu and her family moved into a rented house near a newly-opened school. With about Rs.100 collected from her father’s friends, Liu and her mother began selling homemade momos. “We bought 2 kg maida, 1kg pork and onions. After dinner, we would steam the momos and again the next morning, and sell it to the school children,” she says.

While the earning was barely enough for the family of six, there were days when they couldn’t sell any. But instead of wasting the momos, Liu recalls that her mother made all her siblings finish the day’s produce, “My mother used to go around trying to sell them anyway, but some remained unsold. So, she would make the five of us stand in line together, put five momos on a plate and say, ‘Sit there and eat.’”

When Liu started school, she was put in class six — even though she had been out of touch with education for five years. While Liu scraped through class six to class nine, she eventually dropped out of school when she reached class ten unable to cope with the difficulty. She aspired to become a nurse, and trained briefly. But she was married off, and she moved to Kolkata soon after.

Over the next five years, after her three children were born, Liu recalls her urge to start something of her own to support her family, considering that her husband’s tannery business wasn’t doing very well either. She began buying leather chemicals and selling them elsewhere. “At least this way, I could pay my son’s school fees.” Later, she opened a beauty parlour and picked up the skills, despite no background in beauty and hairdressing.

The Entrepreneur within

In 1991, Liu finally rented out her beauty parlour for Rs.2,500 after working for four years. By then, she had her eye on a house that would soon become Kim Ling. The house then belonged to her aunt-in-law’s grand-daughter. “I told her that I would put some machinery there. I had lied because had I told her I wanted to build a restaurant, she would have refused to sell it to me,” Liu says. She was eventually handed the property after negotiating for Rs.10 lakh in March that year. For that, her brothers and parents offered about Rs.8 lakh and she borrowed another Rs.3 lakh from her friends.

But the restaurant was in need of much renovation. “My one wish was that the restaurant should be air-conditioned. So, we rented an AC for Rs.5,000 every year,” she says. Two months later, Kim Ling started out as an eight-seater restaurant in Tangra, otherwise known as Chinatown, with one staff member besides Liu’s mother and brother. Unfortunately, she got into a quarrel with a customer on the first-day. “We did not have a menu card. All the orders were charged as per local charges, and the customer refused to pay us,” she explains. Exasperated, Liu offered to charge him nothing. “If you want to pay, pay me that much or else leave,” Liu recalls telling him.

It was still a rocky road to success and they were often hounded by local goons, as well as police officers demanding to see their license. Liu says that rather than fearing them, she befriended the police. “If I’m feeling scared what’s the point of doing business. I had to stay strong because I had to do a lot of work by myself,” she says. Her courage cannot be lauded enough, seeing how she dared to keep her restaurant open even during the curfew of the 1992 riots. Her business took a hit on days the curfew stretched for six to eight hours or more. “I had debt to repay. All the restaurants would be closed, but I was the only one open for my business’ sake,” she says.

In 1993, she bought Mandarin from her cousin brother for about Rs.20 lakh. Mandarin, which was originally launched in 1970 in Lansdowne, lost business over the years but Liu took upon the task to rebuild it. “I reduced the price of the food and ensured that its quality was at par with the others,” she says.

Over the next few years, she went on to launch three more restaurants. In 1998 came Beijing in Tangra, for which she bought the plot in three parts, over three years. “All my friends helped out with Rs.1 lakh to Rs.2 lakh each. But mostly, I saved up bit-by-bit from my two other restaurants,” she adds. Despite constant financial help from her friends and parents, the biggest investment so far, she says, was starting Tung Fong in 2001. Liu took out a hefty Rs.75 lakh bank loan to buy an old shop selling salami in Park Street. Eight months were spent in renovating it. Later in 2013, Mandarin’s second outlet was unveiled on Lake View Road. From earning Rs.600-2,000 every day from each restaurant back in the day to about 250 staff working under her now — Liu has come a long way. Her restaurants can easily host 100-250 foodies now.

But clearly, the restaurants weren’t enough to tame her impulses to start something new. Liu has been supplying sand and stone chips to Kolkata Municipal Corporation for three years now. “I am in business. I want to look at wherever there is an opportunity to make money,” she says. Some time ago, Liu went to China to explore options to import cheap electronics from China and sell here. “Smart televisions, for example, are very, very cheap in China. But I figured, the electronics market is intensely competitive, so I dropped the idea.” Liu says, she will soon wind up her construction business as it is a “bad” business — the payment cycles are too long. Smaller players can’t survive with six-month payment cycles. “You should choose a business that you can handle. I could cook and restaurant is a cash business, so it worked well for me,” she adds.

Embracing the past

Despite an unlikely journey, Liu owes her success to all the hardships she had faced in her life — be it growing up in a prison or near-starvation days post-internment. All her years of extreme poverty made her both gritty and enterprising. At the Deoli camp, she would teach the other children to sing, dance and enact Ramayana, and some elders how to plant onions and potatoes. “Leadership is about how to guide them, taking care of them and how to teach them. Only now do I know that back then I had become one,” she says.

No matter what curveballs life throws, Liu is not one to shy away from facing them head-on. In a competitive industry like restaurants, she continues to stay true to the original Chinese flavours. As for what’s next on her list, she would like to open more Beijing outlets and perhaps, move into other cities as well. Clearly, when nothing could defeat her spirits so far, it would take a lot more to beat the ‘Don of Chinatown’.